|

The U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals recently reaffirmed that a claimant must give the employer notice of a settlement or judgment of a third party lawsuit arising from the work-related injury, or risk losing entitlement to benefits. In Parfait v. Dir., OWCP, 16-60662 (5th Cir. Sep. 11, 2018), 2018 U.S. App. LEXIS 25736, the claimant maintained that the employer had notice of the settlement because the claimant invited the employer to attend a mediation. The claimant further maintained that the employer had notice of the judgment he obtained against a third party through the filing of the judgment in the public record.

The Fifth Circuit decided this case under Section 33(g) of the Act, and found that the claimant had not provided adequate notice as required by this section. As the Fifth Circuit explained, “Section 33(g) … requires the employee to obtain written approval of certain third-party settlements and to give notice of all third-party settlements and judgments, [and] is designed to ensure that the employer’s rights are protected in the settlement and to prevent the claimant from unilaterally bargaining away funds to which the employer or its carrier might be entitled …. [T]he notice requirement enables an employer to protect its right to set off the settlement amount against its future obligations and its right to reimbursement of its previous payments from the settlement proceeds. Further, it ensures against fraudulent double recovery by the employee.” The Fifth Circuit upheld the application of Section 33(g) to bar the Claimant from benefits. The court relied upon the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Estate of Cowart v. Nicklos Drilling Co., 505 U.S. 469 (1992), which had emphasized the importance of the Section 33(g) scheme of notice and approval of settlement.

0 Comments

The Defense Base Act and the Longshore Act preempt claims for retaliatory discharge, but not contractual claims arising from the discharge, according to the U.S. District of Columbia Court of Appeals.

In Sickle v. Torres Advanced Enterprise Solutions, LLC, 884 F.3d 338 (D.C. Cir. 2018), 52 BRBS 7(CRT), Matthew Elliot and David Sickle worked in Iraq for Torres Advanced Enterprise Solutions. Elliot sustained an injury to his back, and Sickle, a medic, documented and treated the injury, and recommended that Elliot return to the U.S. for further treatment. Torres learned that Elliot was seeking workers’ compensation and terminated Elliot, alleging that his position in Iraq was no longer needed. Thereafter, according to Sickle, Torres began to “‘threaten and intimidate’ him, insisting that he recant his support for Elliot’s workers’ compensation claim.” Soon after these threats, Sickle was fired. Elliot was awarded benefits, but both men filed suit in federal district court, alleging retaliatory discharge, breach of contract, and other common law claims. Torres moved to dismiss the complaint, alleging preemption under the Defense Base Act and the Longshore Act. The district court agreed and dismissed the complaint, determining that Sickle and Elliot failed to exhaust their administrative remedies and that their common law claims were preempted. On appeal, the D.C. Circuit ruled that Elliot’s tort claims were preempted because they arose out of his application for workers’ compensation benefits. However, the D.C. Circuit found that his contract claims, arising out of Torres’ failure to adhere to the employment contract when it fired Elliot, were viable. As to Sickle, the D.C. Circuit determined that none of his claim were preempted, because his claims were “divorced from any claim for benefits.” As a predicate to its determination, the D.C. Circuit determined that preemption is not a jurisdictional issue, but instead is a merits-based defense. The court found that preemption “does not implicate the power of the forum to adjudicate the dispute,” but instead is an affirmative defense. “Preemption under the Base Act and Longshore Act speaks to the legal viability of a plaintiff’s claim, not the power of the court to act.” Examining the preemption issue the court determined that neither the Defense Base Act nor the Longshore Act expressly preempt state tort or contract claims. However, the court believed that the two acts impliedly preempt state common law claims arising from workplace injuries, as part of the “legislated compromise” of surrendering tort claims in exchange for “an expeditious statutory remedy.” However, the court stated that implied preemption does “‘not preclude [individuals] from pursuing claims that arise independently of a statutory entitlement to benefits, such as a common-law assault claim,’ or a ‘breach of contract’ claim ‘based on a separate agreement to make payments … to provide care.’” Summarizing its decision, the D.C. Circuit observed that the “touchstone for implied preemption under the Base Act is a claim’s nexus to the statutory benefits scheme. Because Elliott sought and obtained workers’ compensation under the Base Act, his tort claims arising from that benefits process are preempted, but his independent claim of contractual injury is not. Sickle, for his part, never set foot into the Base Act’s regulatory arena, so both his tort and contract claims can proceed.” The Benefits Review Board recently resolved a dispute discovery issue by holding that an administrative law judge possesses the authority to order a claimant to sign a medical release. However, the Board also provided rules limiting the scope of those releases.

As the Board explained in Mugerwa v. Aegis Defense Services, BRB No. 17-0407 (4/27/18), lower federal courts are split as to whether judges possess the authority to compel a plaintiff to sign medical releases. These courts generally consider the competing issues concerning the plaintiffs’ privacy and fairness to the defendant. Without much analysis, the Board held that “[w]eighing the competing interests identified in these cases, we hold that administrative law judges have the authority to compel claimants to sign narrowly-tailored medical releases when it is reasonable under the circumstances to do so.” As a predicate to this holding, the Board first determined that medical release forms are a permitted method of discovery, because of the broad range of the discovery methods and the authority of administrative law judges. Having determined that the ALJ could order the claimant to sign a medical release, the Board nevertheless restricted the scope of those releases, providing rules that no doubt guide the use of releases in the future. The Board stated: 1. The “employer must first establish a reasonable inference of the existence of additional relevant records in light of claimant’s assertion that he has produced all relevant records.” The Board added that “in the face of a denial of the existence of or control over documents, the requesting party must produce specific evidence challenging the assertion.” 2. “If the administrative law judge finds that claimant has acted in good faith by producing his relevant medical records and employer has not shown the likely existence, relevance, and necessity of the additional requested medical information, the medical release forms are unnecessary, and the administrative law judge should deny employer’s motion to compel.” 3. “If, however, the administrative law judge finds that claimant has acted in good faith but employer has shown the relevance and necessity of medical information held by a medical provider, or if employer establishes claimant has not acted in good faith, then the medical releases may be warranted.” 4. “If they are needed, the administrative law judge must greatly narrow their scope or must order the parties to work together to generate mutually-agreeable medical release forms. If claimant refuses to sign the narrowed medical release forms, then the administrative law judge may grant employer’s motion to compel.” This case arose under the Defense Base Act, and involved a Ugandan citizen injured in Afghanistan. The employer argued that the releases were the only manner it had to secure medical records, because the administrative law judge could not compel a subpoena in a foreign country. In a relatively unusual decision, a panel of the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the Administrative Law Judge and the Benefits Review Board solely on its interpretation of the testimony of the employer’s vocational expert.

Admittedly, both the ALJ and the Board struggled with the vocational expert’s testimony, but ultimately concluded that the evidence demonstrated that the claimant could obtain work as a tower clerk. The ALJ originally held that the proof of the availability of this job was speculative, but he reversed himself and found the job reasonably available at least three days a week. The Board upheld this determination in a split decision. The Ninth Circuit reversed, finding the conclusion that the job was available unsupported by substantial evidence. The Ninth Circuit’s unreported decision was also close, having been decided on a 2-1 split. See Colaruotolo v. SSA Containers, Inc., 16-72856 (9th Cir. 4/19/18), 2018 U.S. App. LEXIS 9878. In reaching its decision, the Ninth Circuit observed that the vocational expert testified only that the tower clerk job “could” be available to the claimant. The Court also noted that the vocational expert testified that the tower clerk position was affected by the “politics” of the waterfront, and the availability of the job was “difficult to nail down.” Finally, the Court found “most telling” that the vocational expert agreed with the claimant’s counsel that the job opening was “actually speculative given all the inanimate forces.” The U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals recently denied a claimant's Petition for Review of the denial of her modification proceeding. In Tyler v. Main Industries, Inc., 17-2021 (4th Cir. 4/2/18), an unpublished decision, the Fourth Circuit refused to review the Benefits Review Board's decision affirming the administrative law judge's dismissal of the claimant's modification request. The ALJ had determined that the modification proceeding was untimely, based on the following facts. On August 21, 2008, the claimant filed a claim for injuries to her tailbone, back, neck and right ankle which she allegedly sustained on July 31, 2008, while working for her employer. In a decision and order dated December 12, 2011, the ALJ found the claimant was entitled to temporary total disability benefits through December 8, 2008. The BRB affirmed this decision on December 17, 2012. On January 26, 2015, the claimant filed a motion for Section 22 modification. The BRB noted that a Section 22 modification request must be filed within one year of the last payment of compensation, or, if a claim is denied, one year from the date the decision becomes final. As a result, a modification request must be filed within one year after the conclusion of the appellate process. As the claimant filed her modification request more than one year after December 17, 2012, the ALJ ruled it was untimely. The BRB affirmed the ALJ's determination. The Fourth Circuit denied a petition for review, finding the BRB decision "based upon substantial evidence and ... without reversible error."

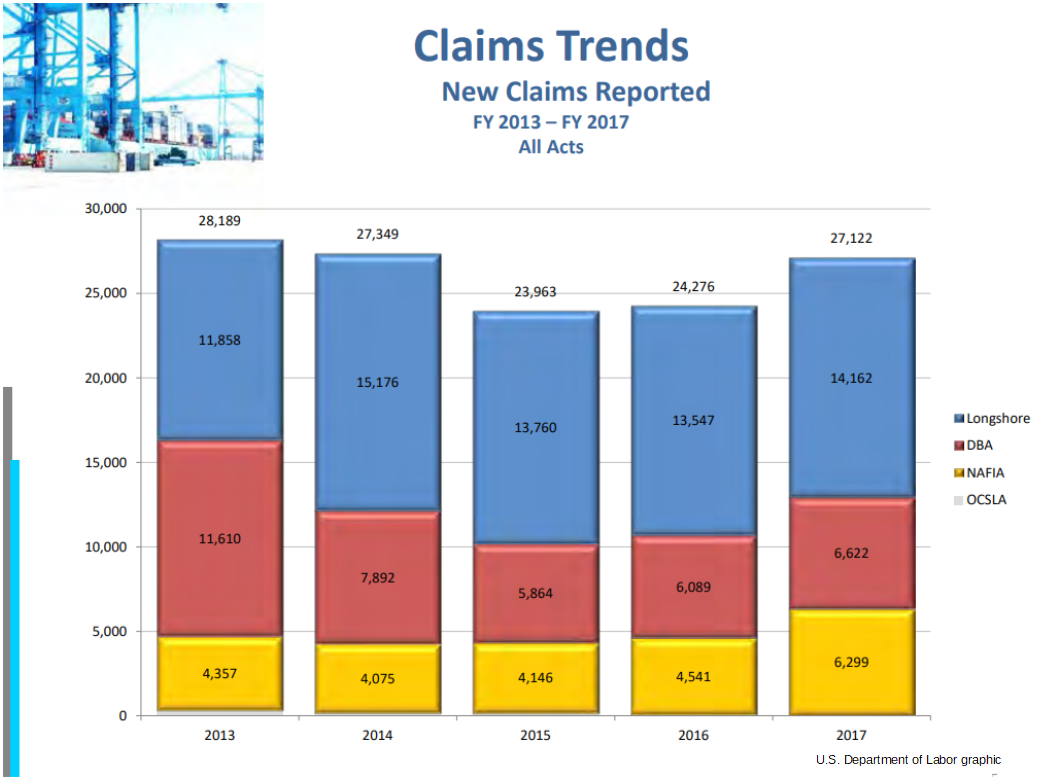

The Longshore Division of the U.S. Department of Labor saw an increase in new claims reported in fiscal year 2017. According to the Division, 27,122 new claims were reported in 2017, a jump from the 24,276 claims reported in 2016. The majority of new claims, 52 percent, were reported in traditional longshore cases. Claims arising under the Defense Base Act formed the next largest group of new claims. Offshore cases arising under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act comprised less than one percent of all new claims.

The U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals refused to disturb a ruling by the Benefits Review Board that attorneys' fees were not owed when a claimant settled his Longshore claim for no money.

In a March 5, 2018, unpublished decision in Castro and Dupree v. SSA Terminals, LLC, 16-73170 (9th Cir. 2018), the Ninth Circuit denied the petition for review of the claimant's former attorney of the dismissal of his fee petition. Earlier, the Board had affirmed the administrative law judge's denial of the claimant's attorney's fee petition. The dispute arose after the attorney withdrew from representation of the claimant. The claimant then settled his claim for Longshore benefits and his companion claim for California state workers' compensation benefits. The claimant settled his state claim for $4,000. After further negotiations, the claimant agreed to settle the Longshore claim for no additional funds, with the employer claiming credit under Section 3(e) for the $4,000 paid in the state claim. Additionally, the settlement specified that the claimant "will receive a lump sum payment of $0.00" to settle his Longshore claim. After these settlements, the claimant's attorney filed a fee petition The ALJ concluded that no attorney fee was owed under Section 28(a) because there was no successful prosecution of the claim. The Board affirmed, noting that a "successful prosecution" of a claim, as required by Section 28(a), requires the claimant's attorney to obtain "some actual relief that 'materially alters the legal relationship between the parties by modifying the defendant's behavior in a way that directly benefits the plaintiff.'" Because the settlement agreement recited that the claimant received no additional money to settle his Longshore claim, the ALJ ruled that the employer had no liability to the claimant and the employer's behavior to the claimant was not modified in any way. Because the ALJ interpreted the settlement as proving that the employer had no liability to the claimant, the ALJ found that the claimed Section 3(e) credit was moot. The Ninth Circuit confirmed the ruling by the ALJ and the Board by denying the attorney's petition for review. The court accepted that substantial evidence supported the conclusion that the parties did not intend for the $4,000 payment to serve as consideration for the release of the claimant's Longshore claim. Moreover, recognizing the likelihood that the "parties structured the agreement to avoid fees under the Act," the court ruled that such an agreement was permissible. The Longshore Division of the U.S. Department of Labor has announced that it will now accept initial filings in new claims by facsimile. As of March 1, 2018, initial "case create" forms may be submitted to the Longshore Division through a new fax number, (202) 513-6814. The "case create," forms, which initiate a claim in the Longshore Division, include Form LS-201 (Notice of Employee's Injury or Death); LS-202 (Employer's First Report of Injury or Occupational Illness); LS-203 (Employee's Claim for Compensation) and the LS-262 (Claim for Death Benefits).

In another change, the case create forms may be submitted by mail to the Jacksonville Office. Prior to March 1, 2018, all case create forms had to be mailed to the New York District Office. The Jacksonville Office address for submitting case create forms is: U.S. Department of Labor Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs Division of Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation 400 West Bay Street, Suite 63A, Box 28 Jacksonville, FL 32202 After a case is created and assigned an OWCP number, all forms and other correspondence and documentation may be submitted through the Division's online portal, SEAPortal. Submissions by mail should go to the Jacksonville Office address. These new procedures apply to all new claims filed under the Longshore Act and all its extensions. The Longshore Division published an industry notice describing these new procedures in detail, which may be read here. The Benefits Review Board recently reminded employers about the difficulty in taking advantage of Section 3(c) of the Act, which disallows compensation when the employee’s injury occurs solely through the employee’s willful intent to cause the injury.

In Jarrett v. CP&O, LLC, 51 BRBS 41; BRB No. 17-0384 (12/3/17), the administrative law judge, after hearing the witnesses and evaluating the evidence, accepted the employer’s argument that a shuttle truck driver willfully caused his own injury by placing his truck in a position to be struck by another truck. The accident occurred early in the morning in a staging area of a port. The claimant attempted to drive his truck around another truck that was parked in proper position. The other truck started to roll forward, and even though the claimant apparently was driving at an excessive rate of speed, the rear of his truck struck the front of the other truck. A port authority police officer investigated the incident and determined it was an “accident” attributable to the fault of both drivers. After the accident, the employer terminated the driver for having a third accident while operating a work vehicle. At trial, the ALJ gave the claimant the benefit of the Section 20(d) presumption that he did not willfully intend to injure himself, but found that the employer rebutted the presumption. On this basis, the ALJ denied the claim. The ALJ found that the claimant “deliberately and knowingly” cut off the other truck, despite years of experience driving a shuttle truck without having a collision. The ALJ also noted the claimant’s excessive speed at the time of the accident and that the claimant had extensive training operating trucks. The ALJ also believed that the claimant was an “experienced” litigant because he had filed four previous claims and knew he could benefit from the aggravation rule. The Benefits Review Board reversed the ALJ’s decision “as a matter of law.” The Board found that the employer failed to rebut the Section 20(d) presumption because no direct evidence existed that the claimant intended to injure himself. Finding no direct evidence of a willful intent to cause the injury, the Board proceeded to characterize the circumstantial evidence as suggesting only negligent conduct. The Board observed that negligent conduct does not preclude recovery under Section 3(c) of the Act. The Board restated precedent that the purpose of the Act “is inconsistent with any notion that recovery is barred by misconduct which amounts to no more than temporary lapse from duty, conduct immediately irrelevant to the job, contributory negligence, fault, [or] illegality.” The Board also criticized the ALJ’s belief that the claimant’s years of experience implied an intent to cause the accident, noting that the evidence provided that the claimant was terminated for having multiple accidents while operating a truck. Additionally, according to the Board, the police officer’s determination that both drivers caused the accident further militated against finding that the claimant willfully intended to injure himself. Finally, the Board criticized the ALJ’s reliance on the fact that the claimant had filed prior claims. The Board stated that the “mere fact that claimant is aware of his right to seek compensation and exercised that right by filing claims is not evidence of intent to injure himself.” As a result of its findings, the Board reversed the ALJ’s denial of the claim and remanded the claim for further consideration. The Longshore Division of the U.S. Department of Labor has phased out the old form LS-206 and incorporated elements of that form into a revised LS-208. The old form LS-206, entitled "Payment of Compensation Without Award," will no longer be used. Instead, the form LS-208, formerly known as the "Notice of Final Payment or Suspension of Compensation Payments," will serve as the primary form used to report all payments of compensation. The new LS-208 will simply be known as the "Notice of Payments." The Longshore Division's notice regarding this change may be viewed here.

|

Categories

All

© 2018 Ira J. Rosenzweig

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed